I know, I know. We’ve all done it: pressed play on a movie so we don’t have to do a real lesson! But using videos in class can be very productive for teaching spoken language! […]

Teaching Pragmatics with Memes

I recently discovered these wonderful communication-fail memes from PunHubOnline! Beyond being peak comedy for language lovers, these memes highlight a really important point: communication happens far beyond grammar and vocabulary. Pragmatics, the hidden rules that […]

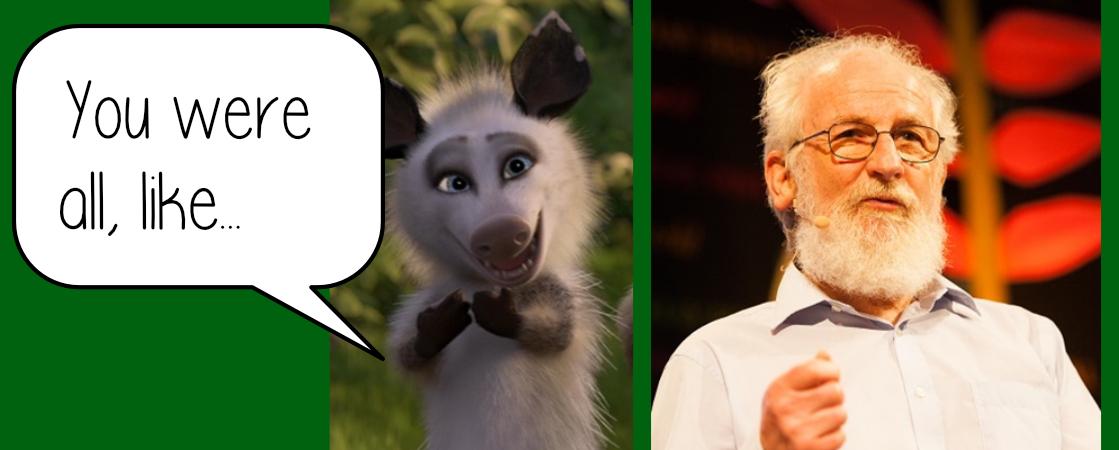

What does “I was, like…” mean?

In the spring, I had the great pleasure of seeing a bit of David Crystal talk at the 2020 Digital Hay Festival. (By the way, if anyone is looking to for a great Christmas present, […]

Improvised Role Plays of Real-World Conversations

Improvisation allows students to prepare for real world situations, but often in regular role plays, the conversation runs more smoothly than in real life. In the real world, people find themselves challenged by awkward situations. […]

Play on Feelings: Using Intonation to Express Emotions

Intonation is notoriously difficult for English learners, yet it is important, particularly in English, for sending emotional messages. The role of intonation in English is complicated but generally English speakers use intonation to express emotion, […]