The History’s Mysteries project is about more than just giving students topics to write about. It also teaches students the critical thinking tools they need to evaluate information and find good sources. That includes distinguishing […]

Guess What’s in the Teacher’s Brain: Asking Better Questions in the Classroom

This post comes from a chapter in a book by Penny Ur or Tessa Woodward about asking questions in the classroom. It’s been a while since I read it, but the essence was that too […]

Creating a Classroom Community Builder Activity

I’m a big proponent of getting to know you activities, not only on the first day of class, but beyond. However, you should definitely do icebreakers or warmers mindfully. Getting to know you activities are […]

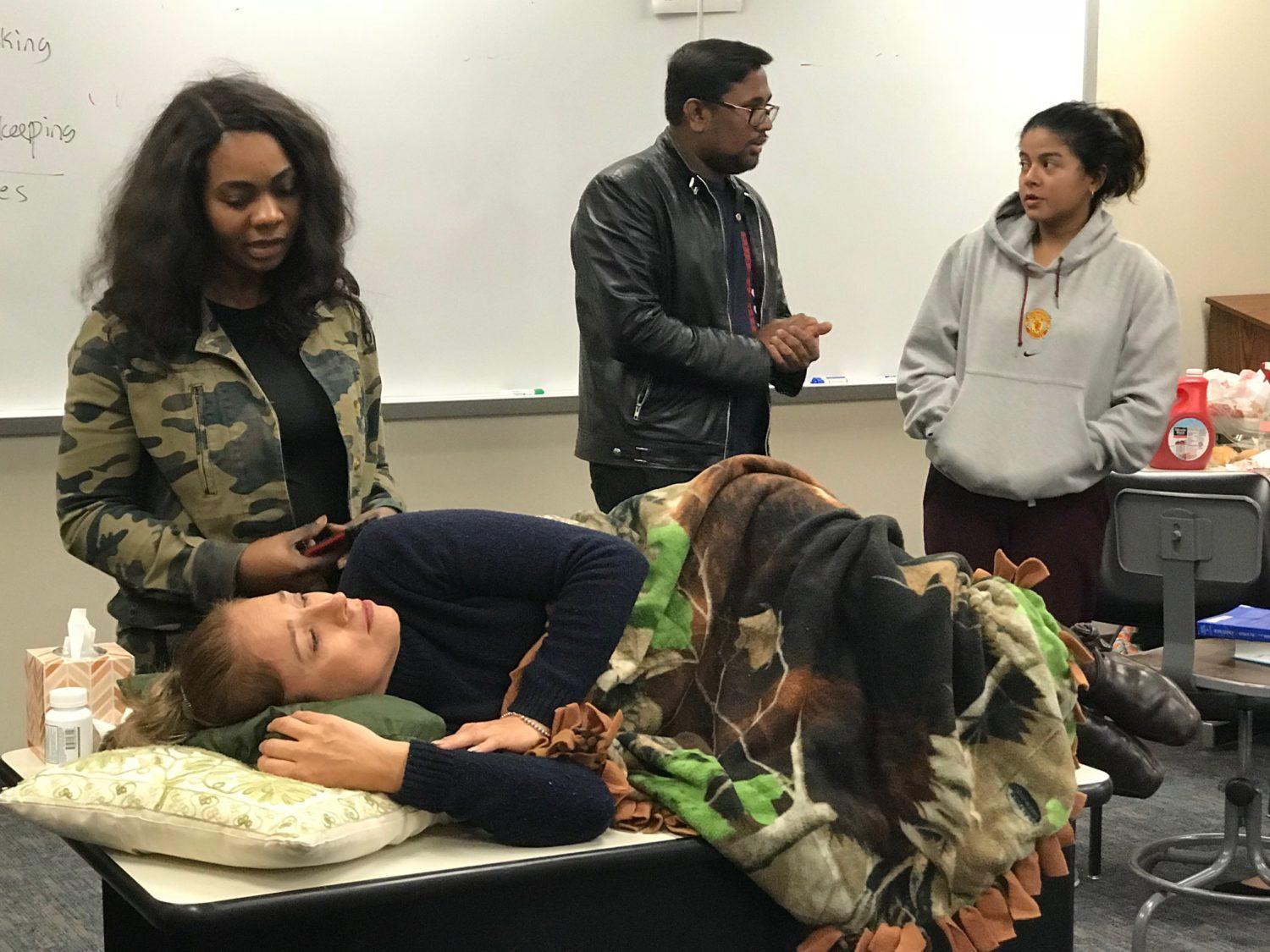

How to do a Play with ESL Students

Producing a play in class can be an amazing learning experience. Drama is more than just a way to cover a book or a fun treat! Plays are a powerful too for teaching speaking skills, […]

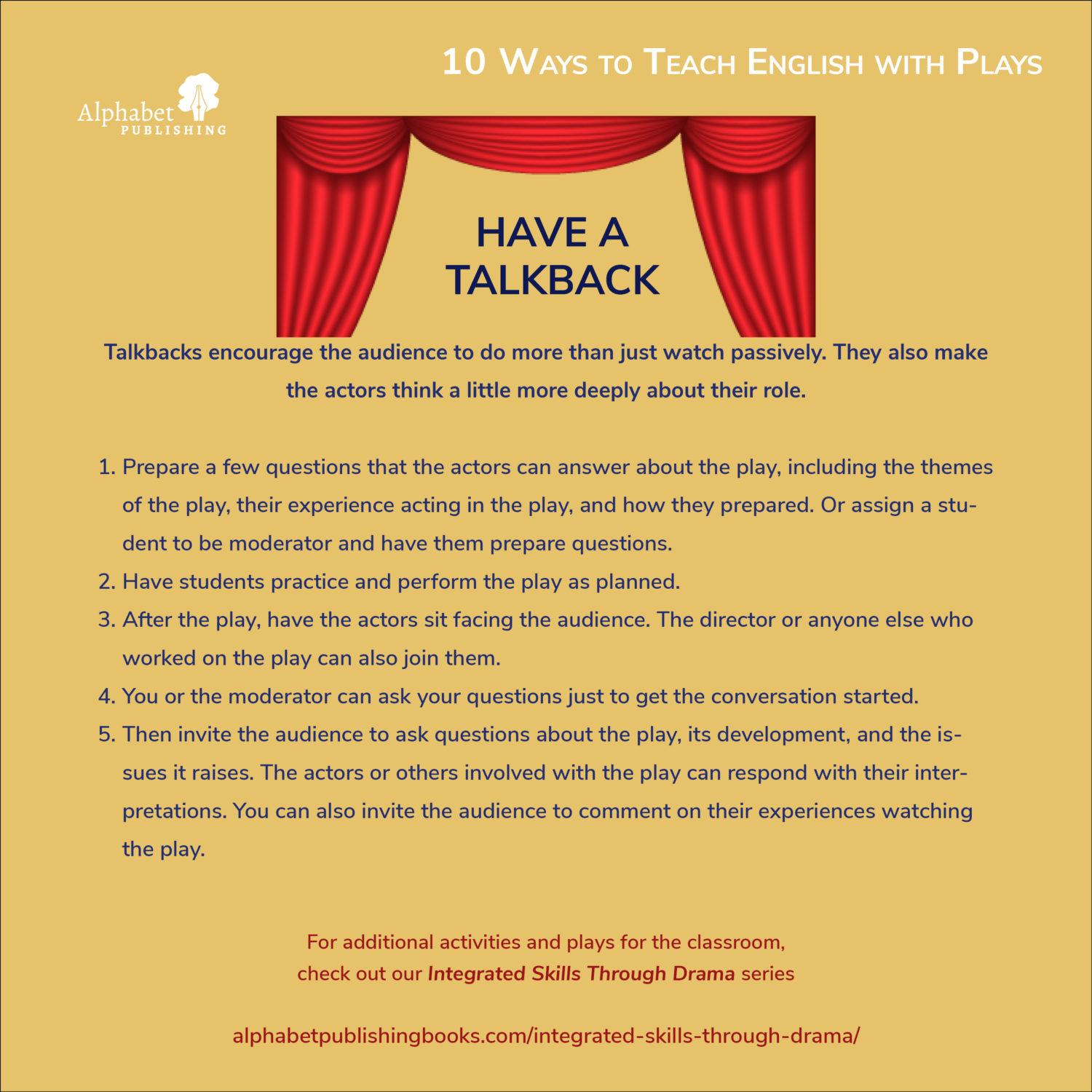

10 Ways to Teach English with Plays

Why teach English with plays? Plays are a natural resource for the English language classroom. They offer opportunities visit and revisit language in action, particularly if the play was written in natural dialogue. Furthermore, when […]