Asking questions happens to be one of my favorite things to do. I used to run a discussion club in Kazakhstan where students could just come and chat about some topic or another. It was […]

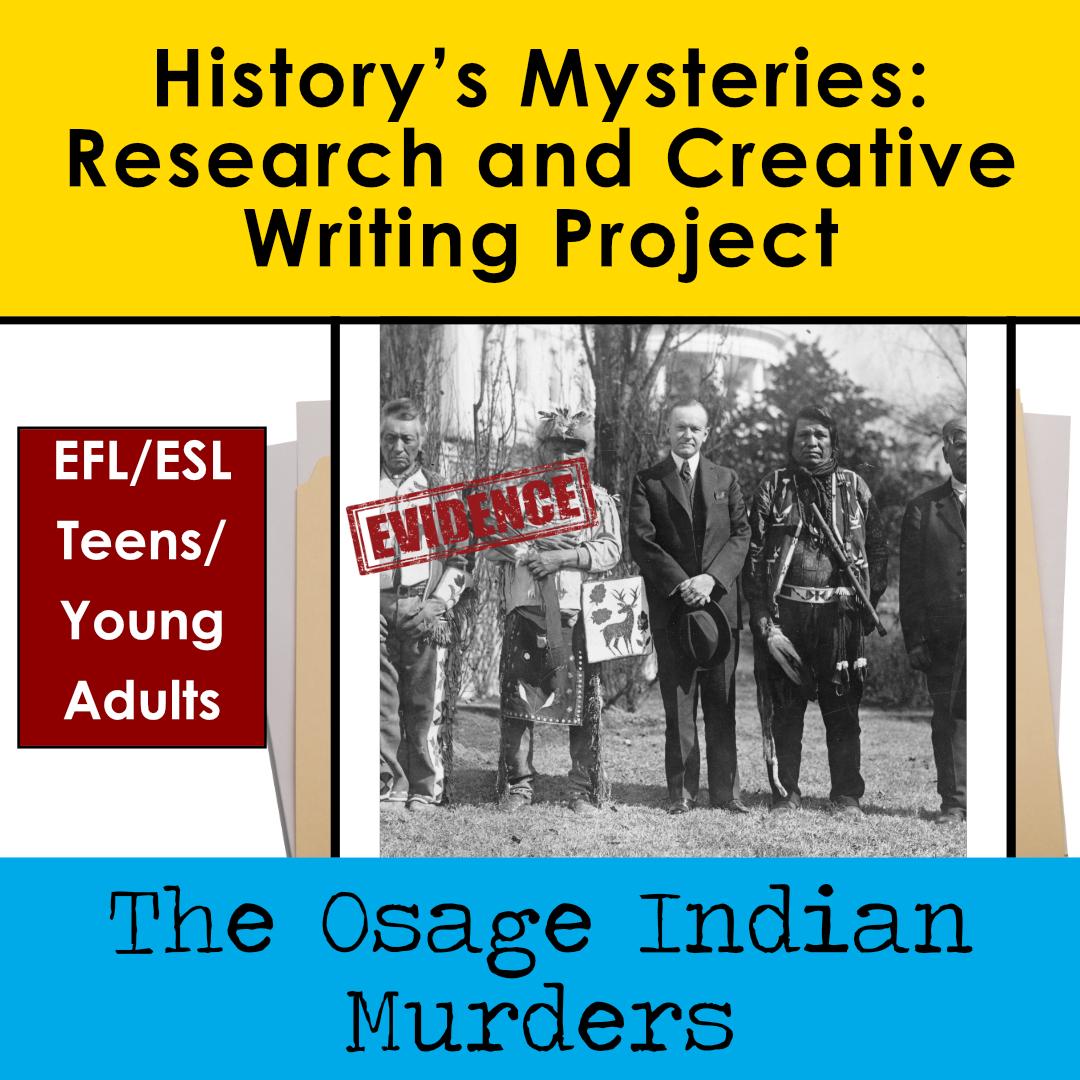

Teaching the Osage Indian Murders

This post describes one of the real historical mysteries discussed in our latest book, History’s Mysteries. This book includes 40 unsolved mysteries from history. Students read a text, discuss and analyze, do research on their own, […]

Logical Fallacies and Critical Thinking

The History’s Mysteries project is about more than just giving students topics to write about. It also teaches students the critical thinking tools they need to evaluate information and find good sources. That includes distinguishing […]