Video is a powerful resource to teach natural conversation to students. Students can benefit from listening to conversations between fluent speakers. In particular, natural, fluent speech provides models of pronunciation and intonation, and how we […]

How to do a Play with ESL Students

Producing a play in class can be an amazing learning experience. Drama is more than just a way to cover a book or a fun treat! Plays are a powerful too for teaching speaking skills, […]

Ways to Make Me Laugh

Humor can be a powerful tool in the classroom. As I’ve written elsewhere before, Humor plays a large role in my teaching. I use jokes to lighten the mood and make learning fun. I use […]

Intonation Sensation: An Activity to Teach Sentence Stress

English speakers use intonation to express meaning, which other languages don’t necessarily do. In some languages, intonation is applied at the sentence level. Intonation may be linked to the meaning of the word. But English […]

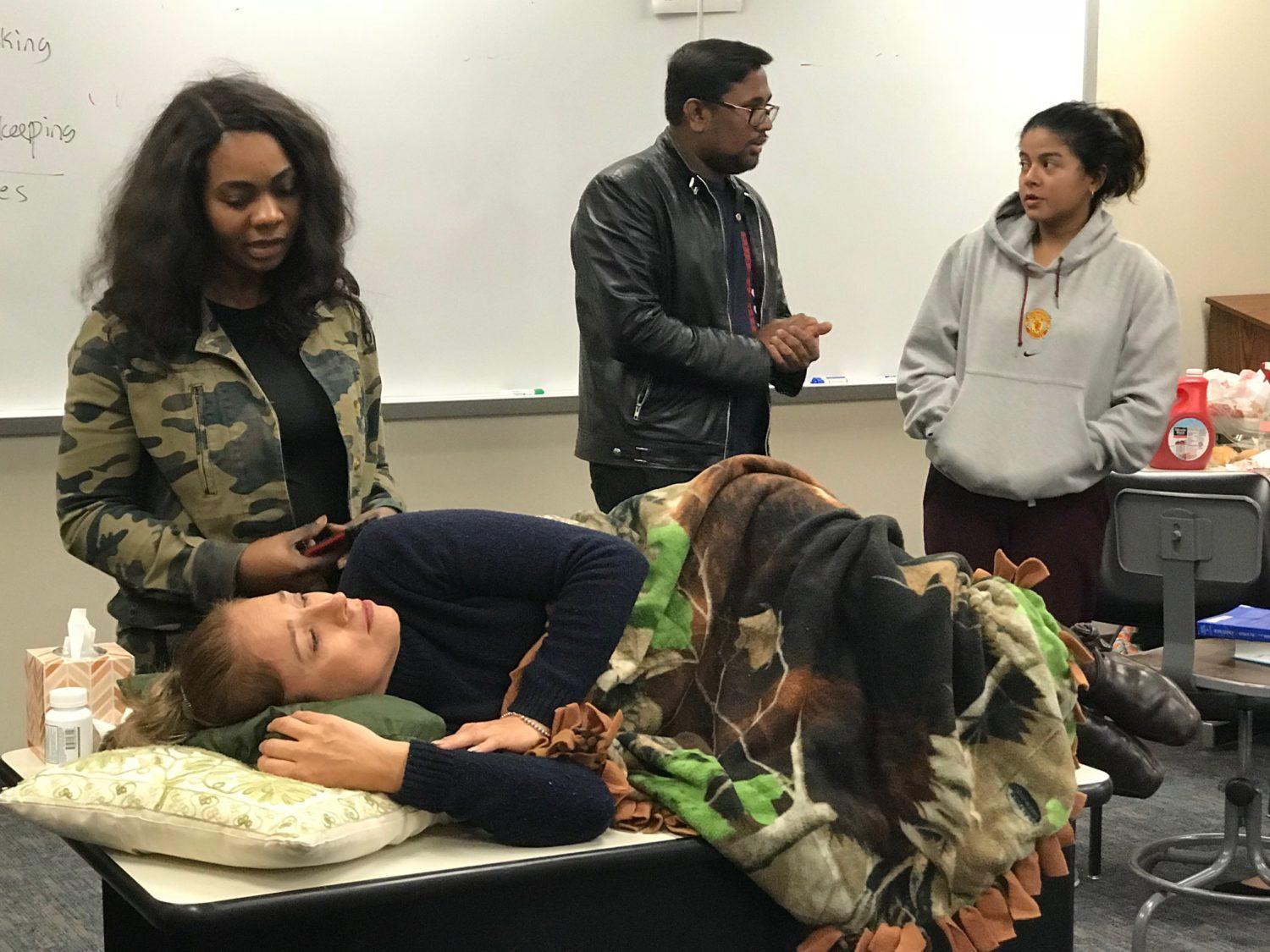

Middle School ESL Drama Activities

In honor of Alice Savage‘s post on Middleweb on exploiting scripts and using role plays in the classroom, I dug up this draft article we worked on together for something or other. There’s some overlap […]

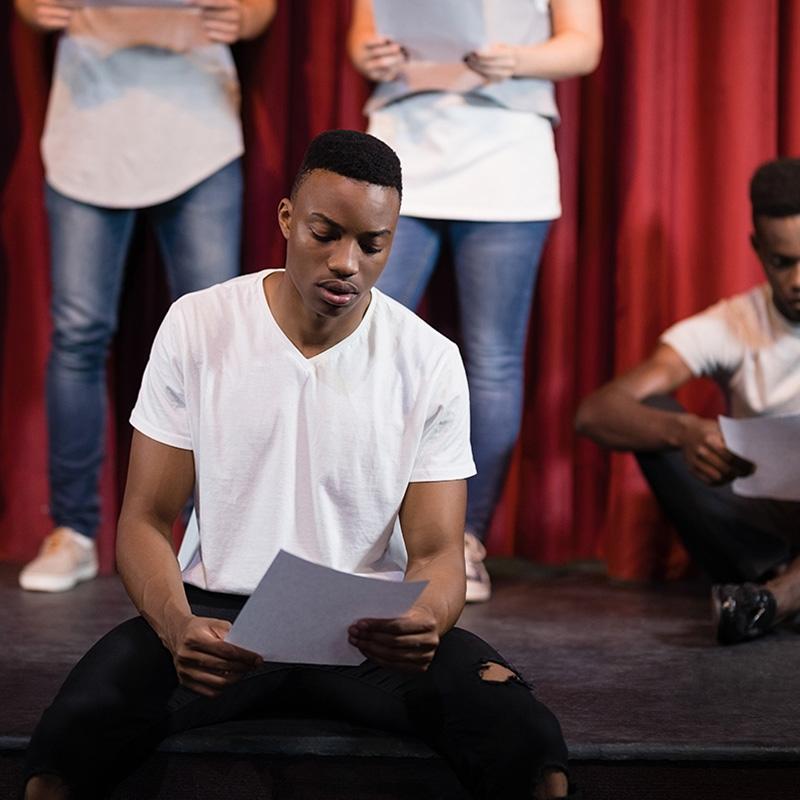

How to Do Reader’s Theater

What is Reader’s Theater? In its simplest form, Reader’s Theater is an activity where students read a play aloud with the scripts in hand. They often do so without having memorized the script. They may […]

Teaching students to be honest: the pragmatics of brutal honesty

We’re not making this up. It’s National Honesty Day and we have some ideas for and ESL lesson about honesty using pragmatics, or the social and cultural rules that determine how we communicate effectively. People […]

10 Ways to Teach English with Plays

Why teach English with plays? Plays are a natural resource for the English language classroom. They offer opportunities visit and revisit language in action, particularly if the play was written in natural dialogue. Furthermore, when […]

Why Do Drama in the Classroom?

Speaking lessons are my favorite lessons to teach. I love writing a really interesting role play and having students go at it. At their best, students get so absorbed in the role and the situation […]