As more and more teachers are turning to online teaching and distance learning for the forseeable future, and students may be considering self-study options, I’d like to introduce our free prompt generating tool, English Prompts, […]

Kinesthetic Grammar Activities: Getting Grammar on the Move!

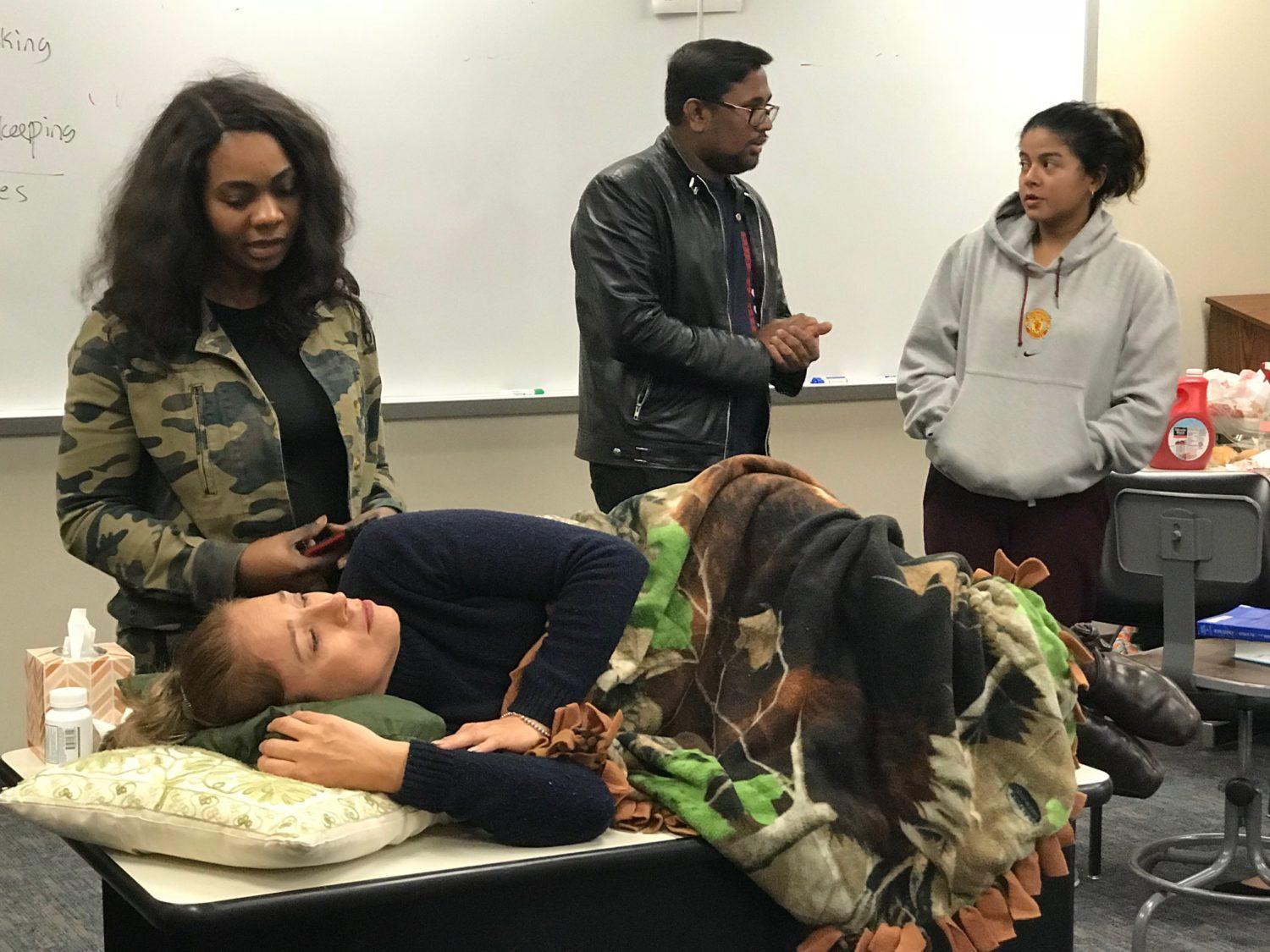

We’re thrilled to be publishing a book on Kinesthetic Grammar Activities from Alice Savage and Colin Ward. Kinesthetic grammar is a great way to practice language dynamically. The benefits are many: Vary the pace of […]

Storytelling for EFL Students

Storytelling is an important skill for EFL students to learn. In fact, being able to tell a story is a helpful human skill as we are constantly constructing narratives to explain what we are doing, […]

Public Speaking in English is Scary. Drama Can Help

Poor Emilio! He seemed like such a confident student, but when he had to give a talk in front of the class, he ran to the bathroom and was sick. Emilio’s case might be extreme, […]

Prosody Practice: Talk Show Activity

Alice Savage, author of the forthcoming The Drama Book, has been doing plays with her students for a while now. But she wanted to know if the prosody practice her students have been doing with […]

Improvised Role Plays of Real-World Conversations

Improvisation allows students to prepare for real world situations, but often in regular role plays, the conversation runs more smoothly than in real life. In the real world, people find themselves challenged by awkward situations. […]

Play on Feelings: Using Intonation to Express Emotions

Intonation is notoriously difficult for English learners, yet it is important, particularly in English, for sending emotional messages. The role of intonation in English is complicated but generally English speakers use intonation to express emotion, […]

Pragmatics is Everywhere

I got this amazing feedback from an educator about one of our drama books and how teaching pragmatics resonates with her students: I introduced the idea of using [Her Own Worst Enemy] in the classroom […]

How to do a Play with ESL Students

Producing a play in class can be an amazing learning experience. Drama is more than just a way to cover a book or a fun treat! Plays are a powerful too for teaching speaking skills, […]

Intonation Sensation: An Activity to Teach Sentence Stress

English speakers use intonation to express meaning, which other languages don’t necessarily do. In some languages, intonation is applied at the sentence level. Intonation may be linked to the meaning of the word. But English […]