This post describes one of the real historical mysteries discussed in our latest book, History’s Mysteries. This book includes 40 unsolved mysteries from history. Students read a text, discuss and analyze, do research on their own, […]

Logical Fallacies and Critical Thinking

The History’s Mysteries project is about more than just giving students topics to write about. It also teaches students the critical thinking tools they need to evaluate information and find good sources. That includes distinguishing […]

Writing Outside the Box: Building Students’ Creativity

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had students tell me that they don’t know how to be creative. They think creativity is a talent that you are born with or not. While it’s […]

How to do Social-Emotional Learning Prompts for ESL

Sometimes the best classroom activities come out of the simplest things. Case in point, these Social-Emotional Learning prompts for ESL students created by Teresa X. Nguyen and illustrated by Tyler Hoang and Nathaniel Cayanan. Each […]

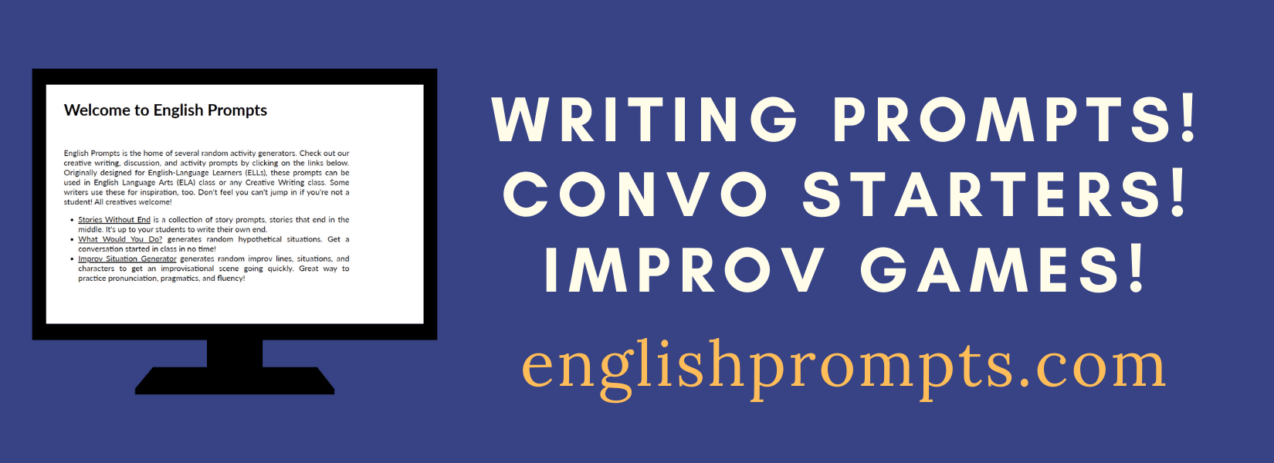

Get Students Writing and Talking!

As more and more teachers are turning to online teaching and distance learning for the forseeable future, and students may be considering self-study options, I’d like to introduce our free prompt generating tool, English Prompts, […]

Stories Without End in the Classroom

I was recently uploading more individual stories without end (from Taylor’s wonderful book) to Teachers Pay Teachers. One of the pieces of information you need to fill out there is how long the material will […]