Intonation is notoriously difficult for English learners, yet it is important, particularly in English, for sending emotional messages. The role of intonation in English is complicated but generally English speakers use intonation to express emotion, […]

Pragmatics is Everywhere

I got this amazing feedback from an educator about one of our drama books and how teaching pragmatics resonates with her students: I introduced the idea of using [Her Own Worst Enemy] in the classroom […]

Slides from TESOL 2019 Presentations

It was an honor to present at the 2019 TESOL Conference and spread the word about using drama and video in language learning. Our author, Taylor Sapp, also presented on using his story prompts to […]

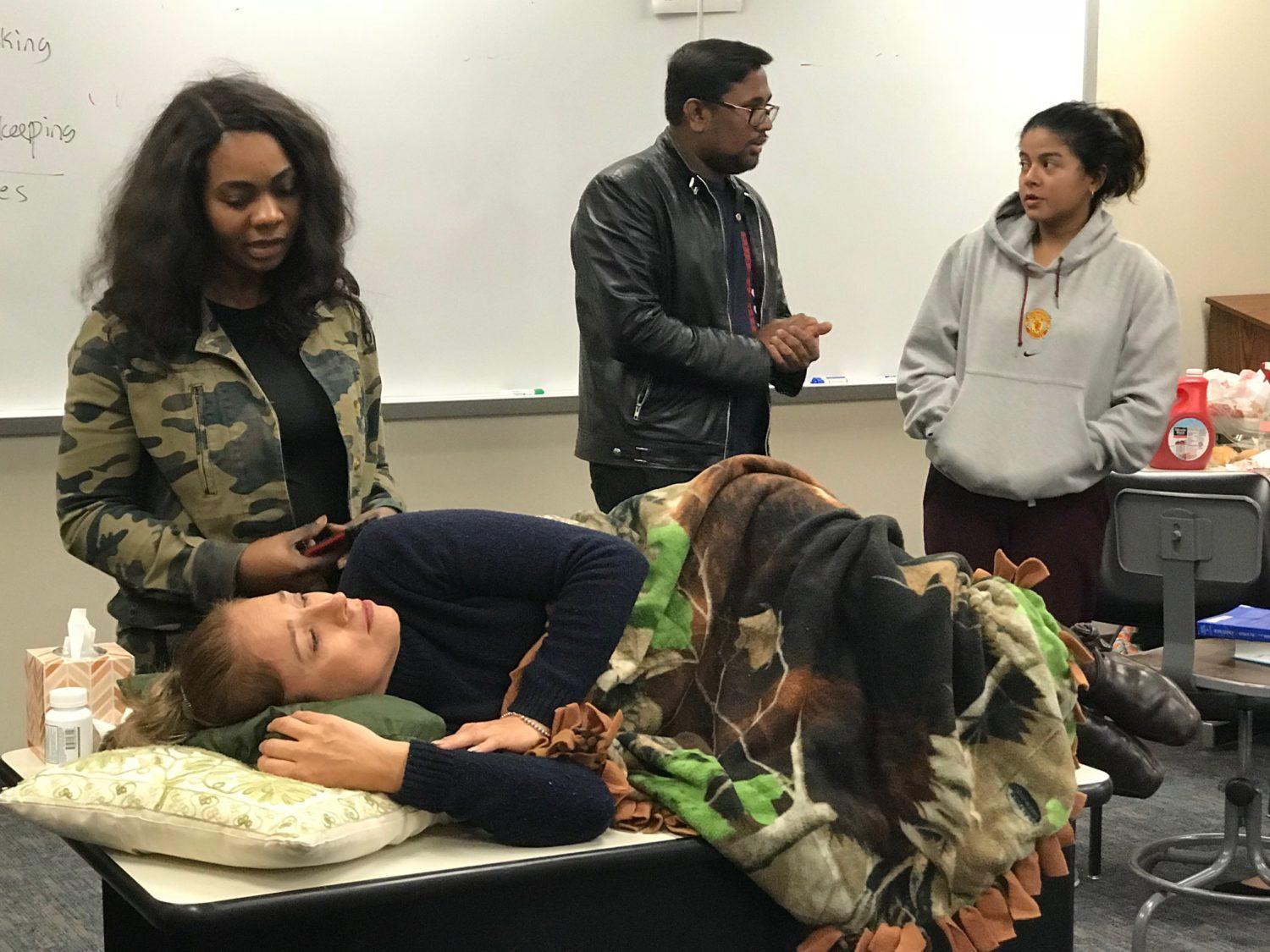

How to Put on a Play in Class

The benefits of drama in the English classroom are surprising. Students learn and practice a variety of acting skills, using their bodies and voices to make meaning. When they put on a play, what to […]

Using Video to Teach Natural Conversation

Video is a powerful resource to teach natural conversation to students. Students can benefit from listening to conversations between fluent speakers. In particular, natural, fluent speech provides models of pronunciation and intonation, and how we […]

How to do a Play with ESL Students

Producing a play in class can be an amazing learning experience. Drama is more than just a way to cover a book or a fun treat! Plays are a powerful too for teaching speaking skills, […]

Middle School ESL Drama Activities

In honor of Alice Savage‘s post on Middleweb on exploiting scripts and using role plays in the classroom, I dug up this draft article we worked on together for something or other. There’s some overlap […]

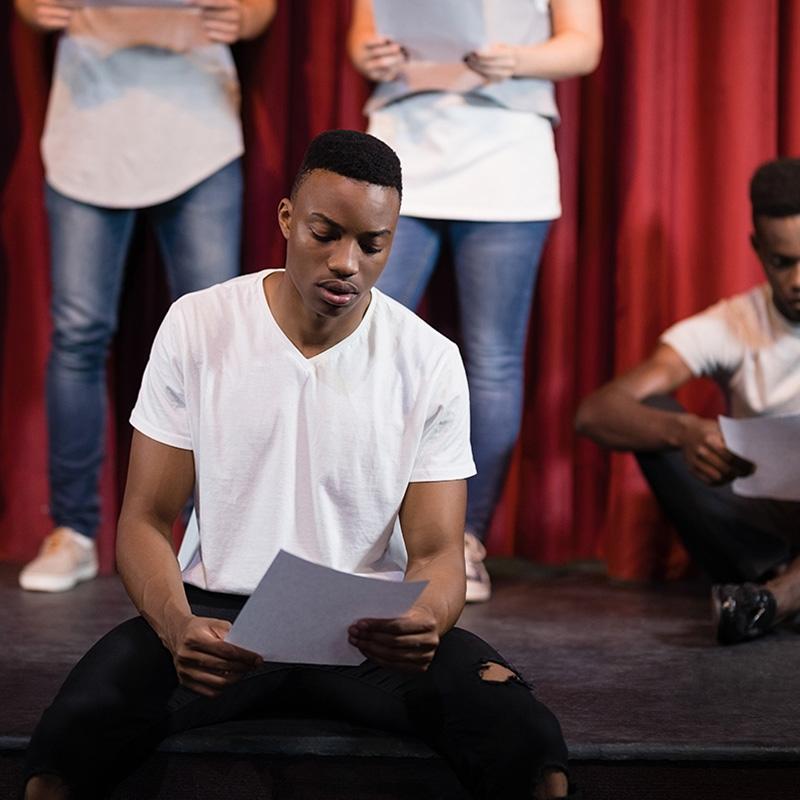

How to Do Reader’s Theater

What is Reader’s Theater? In its simplest form, Reader’s Theater is an activity where students read a play aloud with the scripts in hand. They often do so without having memorized the script. They may […]

Teaching students to be honest: the pragmatics of brutal honesty

We’re not making this up. It’s National Honesty Day and we have some ideas for and ESL lesson about honesty using pragmatics, or the social and cultural rules that determine how we communicate effectively. People […]

Why Do Drama in the Classroom?

Speaking lessons are my favorite lessons to teach. I love writing a really interesting role play and having students go at it. At their best, students get so absorbed in the role and the situation […]